Caterpillars are one of nature’s most relentless eating machines. Found on almost every continent except Antarctica, these small herbivores spend most of their short lives consuming the world around them leaf by leaf. With more than 100,000 known species, caterpillars represent an extraordinary diversity within the order Lepidoptera, the second largest order on earth after beetles.

| Common name | Caterpillar |

|---|

| Taxonomy

|

Class: Insecta

Order: Lepidoptera

|

| Weight / Size | ~3 grams |

|---|

| Lifespan | Few weeks up to 9 months |

|---|

| Population (latest estimate) | Over 100 thousand different species |

|---|

| Habitat | Plants, leaves, organic matter |

|---|

| Range (can be separated if wide, for clarity) | Africa, Asia, Central-America, North-America, South-America, Eurasia, Europe, Oceania, except Antarctica |

|---|

| Diet (one-line summary) | Herbivore |

|---|

| Conservation status | Not assessed by IUCN |

|---|

Physical Characteristics of Caterpillar

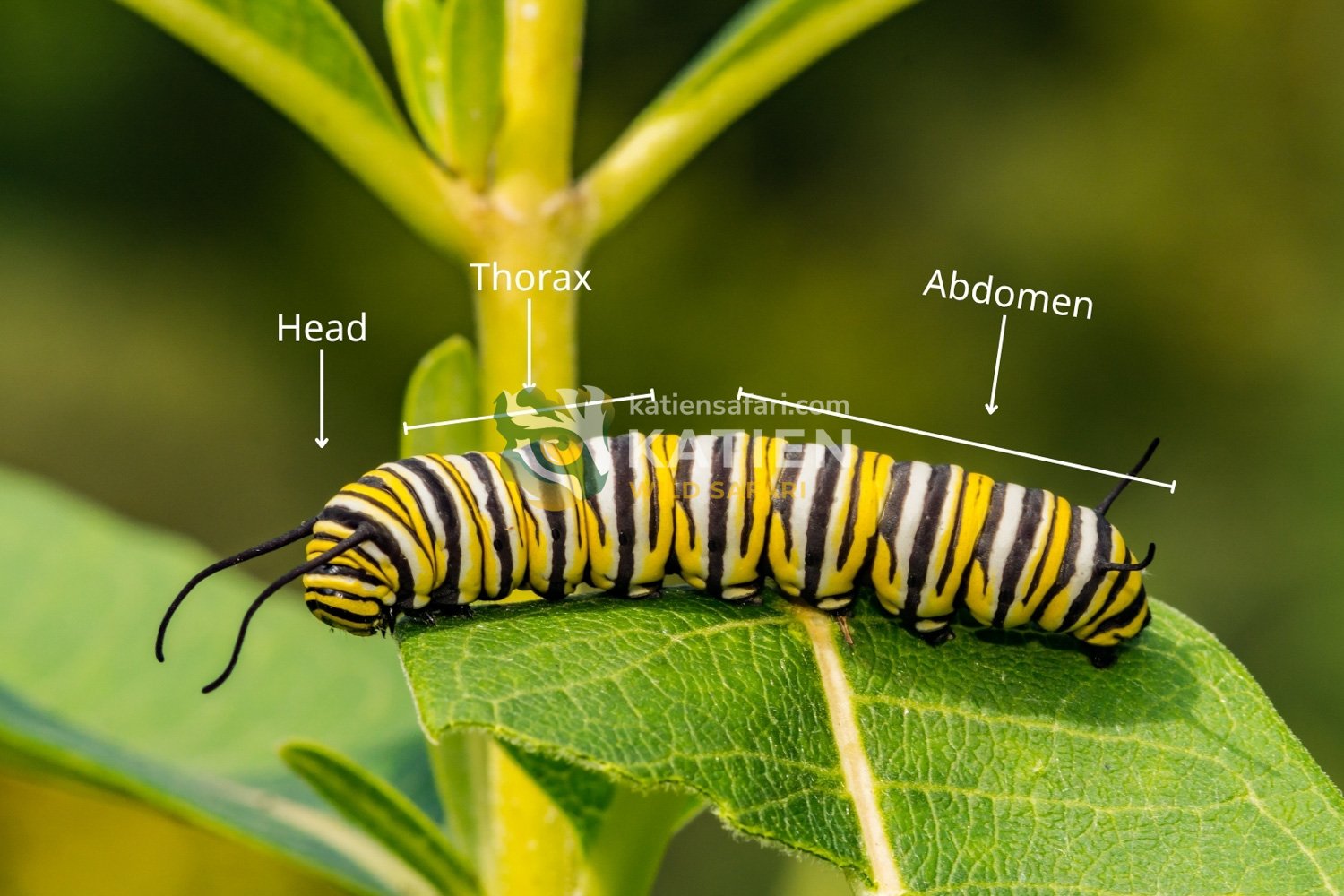

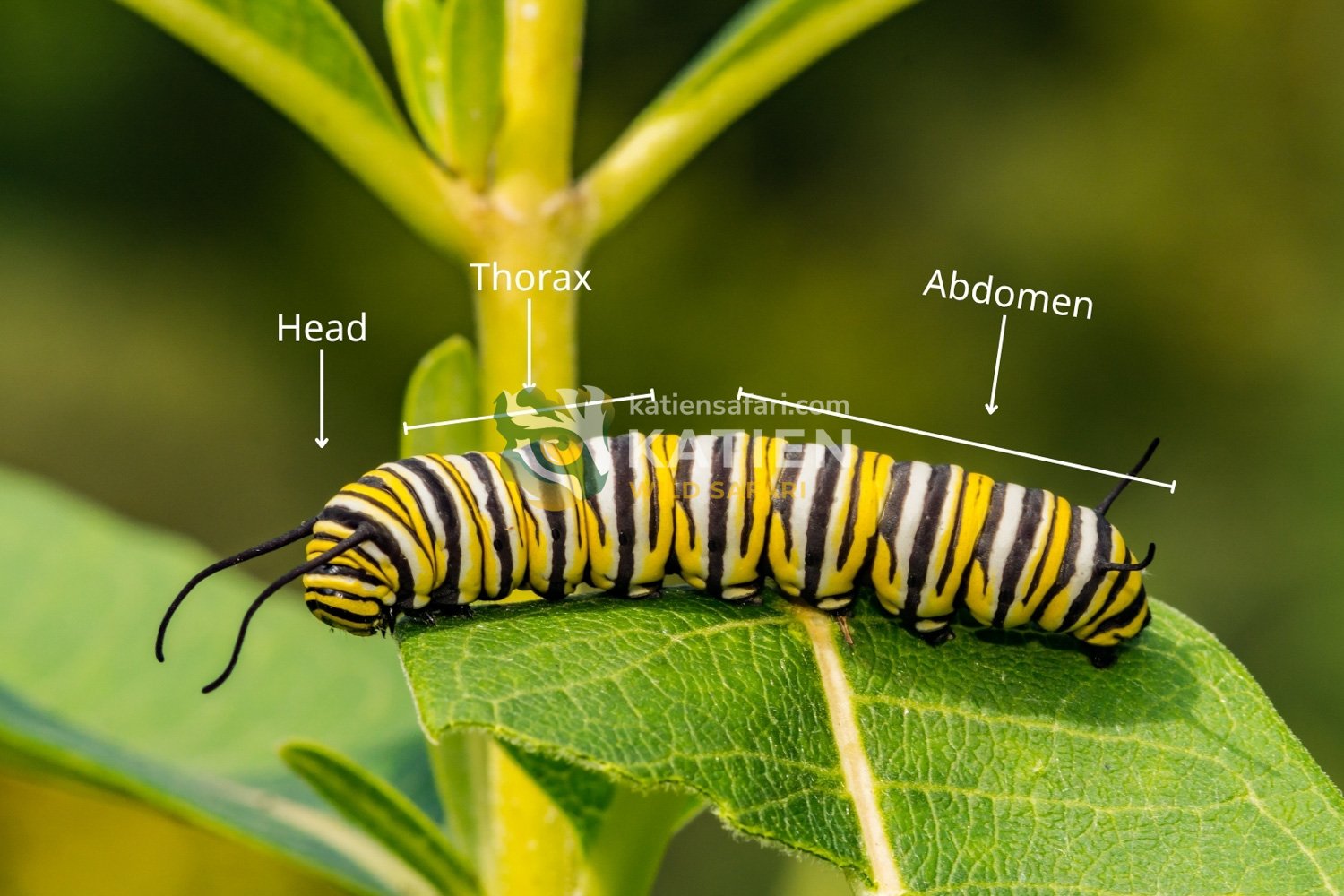

Caterpillars are insects that have 3 body parts and 2 antennae (they are the two long, thin things you see on insects like ants, butterflies, or cockroaches) on their head. The 3 parts are called: The head (the front of the insect's body, where the eyes and antennae are), the thorax (the middle part of the body, between head and abdomen) and the abdomen (the tail end of the body, with the belly and the digestive system).

A caterpillar's body parts

Size, Weight and Lifespan

Caterpillar average size

Caterpillars display an astonishing range of sizes across their many species. Many measure just a fraction of an inch, with the delicate clothes moth caterpillar barely reaching 0.25 inch (0.6 centimeter). Others grow far larger. The hawk moth caterpillar, for example, can stretch to an impressive 4 inches (10 centimeters). A few remarkable species push those limits even further, reaching more than 6 inches in length and earning their place as true giants of the insect world.

Caterpillar body structure

During the brief larval stage, caterpillars undergo astonishing growth. A caterpillar's body can stretch to ten or twenty times their original length, while their weight may increase two to three thousand times which is fueled almost entirely by constant feeding. Caterpillar’s appearance is just as varied as their size. Some caterpillar species display bold colors and intricate patterns, while others blend into their surroundings with muted greens and browns. A few look almost mythical, carrying long, curved, spiky horns along their bodies. Certain caterpillar species even bear protective hairs attached to mild poison sacs. When these hairs brush against human skin, they can cause a burning sting followed by swelling.

Caterpillars are built for this rapid transformation. Their soft, cylindrical bodies stretch easily as they grow, allowing them to reach and feed on distant leaves with surprising agility. Most of their structure is flexible, but several essential parts are reinforced with a hard cuticle. These include: The head capsule, the powerful chewing mandibles, the spiracles arranged along the sides of the body, the short thoracic legs, and the tiny crochets that tip the abdominal prolegs. Together, these features support their remarkable ability to eat, grow, and prepare for metamorphosis.

Caterpillars have two main types of legs. The thoracic legs, located near the head, are short and jointed like those of other insects. Because they are so small, the caterpillar’s mouth stays very close to the leaf surface, making it easier to eat. Behind these are the prolegs, soft and unsegmented legs found on the abdomen. Prolegs help support the caterpillar’s heavy body and allow it to grip leaves and branches firmly. Each one ends in a flat pad with tiny hooks called crochets that act like little anchors.

A caterpillar’s body is dominated by its enormous digestive system. Strong mandibles tear through leaves, sending food into a digestive tract that nearly fills the entire interior. The stomach, or ventriculus, is long, thick, and capable of expanding dramatically thanks to its rounded folds, a design made for processing massive amounts of plant matter. In short, the caterpillar’s cylindrical shape exists largely to hold this very large digestive system.

The head of a caterpillar is followed by 12 or 13 segments. Like all insects, caterpillars have three pairs of permanent legs, one pair on each of the first three segments directly behind the head. These legs are usually hard and jointed. At their tips are tiny claws, but in some caterpillars these are not developed. The caterpillar also has two to five pairs of soft, thick legs that support the rest of its long body. These disappear when it changes into a moth or butterfly. A caterpillar has six tiny beadlike eyes on each side of the head, just above the strong upper jaws. It breathes through nine small openings on each side of its body. These are called tracheae. It also has short antennae.

Caterpillar lifespan

Caterpillars live fast, transformative lives. Some spend only a few weeks in their larval stage, racing through their feeding and growth cycles before entering metamorphosis. Others, depending on species and climate, may remain caterpillars for up to nine months. During this short window, they grow at an extraordinary pace shedding their skin again and again as their bodies expand beyond anything their first form could contain.

Distribution and Habitat

Global Range

Caterpillars are found across nearly every corner of the world, thriving in regions that stretch from Africa and Asia to the vast landscapes of Eurasia and Europe. They occupy the forests of North and South America, the tropical zones of Central America, and the diverse ecosystems of Oceania. With the exception of Antarctica, these larvae have adapted to an extraordinary variety of climates and environments.

Wherever plants grow, caterpillars follow. They live among leaves, stems, and flowers, feeding on fresh vegetation or organic matter on the forest floor. Their habitats range from dense rainforests and open grasslands to backyard gardens and mountain slopes, any place that offers enough plant life to sustain their constant need to feed and grow.

Caterpillar in Vietnam

Vietnam lies at the heart of tropical Southeast Asia, one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. This warm, humid environment supports an exceptional variety of caterpillars. With more than 1,100 recorded butterfly species in the country, the diversity of their larval forms is equally remarkable.

The richest areas for caterpillar diversity span several key regions: the rugged mountains of the Northwest and Northeast, the lush forests of the Truong Son mountain range, and the varied landscapes of the South Central Coast and Southern Vietnam. These habitats provide abundant vegetation and stable climates, creating ideal conditions for caterpillars to thrive in extraordinary numbers and forms.

Caterpillar in Cat Tien National Park

Located about 150 kilometers from Ho Chi Minh City, Cat Tien National Park is one of Southeast Asia’s most biologically rich tropical forests and a UNESCO-designated Biosphere Reserve. Vietnam is home to more than 1,100 butterfly species, and remarkably, Cat Tien National Park shelters more than 450 of them.

The park naturally supports an equally remarkable variety of caterpillars, ranging from widespread species to rare and endemic forms. Its diverse habitats, from moist evergreen forest to bamboo stands and riverine vegetation, provide ideal food plants for butterflies and caterpillars, including swallowtails butterflies (Papilionidae), atlas and wild silkmoths (Saturniidae), and hawk moths (Sphingidae). Their presence reflects the dynamic, ever-growing life that defines Cat Tien’s rainforest ecosystem.

Every year, from late March to early April, the first rains transform Cat Tien National Park into a vibrant sanctuary of butterflies. As the forest is refreshed by new moisture, thousands of butterflies spread their bright wings and fill the air like dancing petals, drifting lightly above the trees and grass like colorful flowers in motion. Along the park’s nearly 10-kilometer forest trail, visitors can witness thousands of butterflies drifting across the path, clustering around puddles, or forming shimmering carpets on the ground, especially in humid, water-rich pockets of the rainforest.

The best time to experience this spectacle is around 8 AM, when warm sunlight filters through the canopy and butterflies begin rising from the forest floor like a colorful, swirling procession. Remarkably unafraid, many will circle close or land gently on a visitor’s shoulder. And for those who want an even closer encounter, here’s a little secret: butterflies here are drawn to the scent of fermented shrimp paste. A dab of it can draw swarms close enough for rare viewing and remarkable macro shots.

Subspecies of Caterpillar

With more than 100,000 different species worldwide, caterpillars represent one of the most diverse groups on Earth. Each species carries its own adaptations, variations in color, size, behavior, and defensive traits shaped by the environment in which it evolves. From tiny leaf-miners hidden inside greenery to large, vividly patterned giants of tropical forests, this immense diversity reflects the caterpillar’s ability to occupy almost every plant-rich habitat on the planet.

Among the countless species, a few stand out for their striking appearance and remarkable adaptations:

- Monarch caterpillar: Vertical stripes of black, white, and yellow-green.

- Spicebush swallowtail: Famous for its dramatic transformation from mimicking bird droppings as a juvenile to developing bright green bodies with large false eye spots that resemble a snake’s head.

- Puss caterpillar: Highly venomous caterpillar, covered in gray and orange hairs, which have venom glands at the base.

- Hickory Horned Devil caterpillar: Vary slightly in color but are commonly blue-green and dramatic red-orange, black-tipped horns that rise from its thoracic segments. Despite its fearsome appearance, this giant species is harmless to humans.

- Saddleback caterpillar: Bright green “saddle” marking set against dark brown ends, a slug-like body shape, and stinging spines that line its sides. Its vivid aposematic colors warn predators of its potent venomous sting.

Behavior and Lifestyle

Caterpillar behavior patterns

Caterpillars don’t walk with their legs like most insects, they propel themselves through waves of muscular contractions that travel from the rear of the body toward the head. These movements created by powerful longitudinal muscle bands allow the caterpillar to advance steadily across leaves, branches, and forest floors. Most species rely on two main locomotion styles: crawling and inching.

Crawling is a forward-moving, anterograde motion and remains the most closely studied form of caterpillar movement. During crawling, pairs of abdominal prolegs lift at the same time, while a wave of stepping motions originates from the terminal segment and travels forward to the thoracic legs. To increase speed, caterpillars shorten the time between each crawl cycle, but the rhythm of the individual steps stays relatively stable.

A caterpillar inches on a branch

Inching, on the other hand, is common among slender, smaller species. These caterpillars anchor themselves with their thoracic legs and the last pair of prolegs. When the rear anchor is pulled forward, the center of the body rises off the surface, forming the characteristic omega Ω-shaped loop. Straightening the loop propels the caterpillar ahead with each measured movement.

Caterpillars also employ rapid, short-term escape motions when threatened. These include rolling, climbing with silk threads, moving backward, or even “galloping,” a surprisingly fast gait. Rolling, for example, can be up to forty times faster than forward crawling an astonishing burst of speed for such a small creature.

As their larval stage nears its end, caterpillars prepare for metamorphosis. When juvenile hormone levels drop and thoracic hormones take over, the body enters its final transformation. Inside the pupa, many larval tissues break down while the structures of the adult butterfly or moth are built. The caterpillar does not simply “turn into” a butterfly. Instead, the developing adult reuses whatever larval organs can be retained such as the heart, tracheal system, and parts of the nervous system while specialized larval features dissolve or are replaced entirely.

Among the most distinctive movers are the Geometridae, often called loopers or measuring worms. These caterpillars reduce or eliminate their middle prolegs, leaving only the thoracic legs and the last abdominal prolegs. Their movement is iconic as they grip with their front legs, pull the rear prolegs forward to form a high arch, then extend the body to advance. Each looped motion carries them a surprising distance, giving them their name as the “measurers” of the insect world.

Caterpillar feeding habits

Caterpillars are voracious eaters, spending nearly every hour of daylight chewing through plant leaves to fuel their rapid growth. Some species go beyond foliage as they feed on honeycomb inside beehives or even on wool from sweaters. Others travel impressive distances in search of the specific host plants they need. Their efficiency is so remarkable that a few moth species, like the Eastern Tent Caterpillar (Malacosoma americanum), do not need to eat at all as adults as all the nutrients required for egg production are stored during the caterpillar stage.

A caterpillar muches plant stems

Although caterpillars are best known as strict plant-eaters, not all follow a vegetarian diet. A small number have abandoned this lifestyle, becoming carnivorous or even parasitic. Wax moth larvae, for instance, invade beehives and consume beeswax and pollen. Other species turn into predators, feeding on aphids, spider eggs, or the larvae of other insects. One extraordinary member of the Lycaenidae family imitates aphids by secreting a sugary liquid to attract ants. Once carried into the ant nest for protection, it feeds on the ants’ own larvae.

In many ways, the caterpillar is a fully equipped digestive machine. Adult butterflies and moths have a limited diet, relying mostly on nectar and possessing only one known digestive enzyme called invertase, which breaks down sucrose. Caterpillars, in contrast, carry a full suite of digestive enzymes, including amylase, maltase, lipase, trypsin, and erepsin, allowing them to break down sugars, starches, fats, and proteins. This biochemical toolkit enables them to process an astonishing range of foods and supports the explosive growth that defines their larval lives.

Do all caterpillars turn into butterflies?

While all caterpillars are destined to transform, some do not turn into butterflies. This is because moths also begin as caterpillars, and have a very similar metamorphosis process. However, the key difference lies in the structure they form for the pupal stage. Caterpillars that will become butterflies form a chrysalis, a hard, smooth casing where the transformation takes place. Moth caterpillars, on the other hand, spin a cocoon, a protective layer made of silk that they weave around themselves before entering the pupa stage. During this stage, the vessel may differ, but the biological miracle within remains one of nature’s most striking transformations.

A colorful moth resting on a flower

Caterpillar predators

Caterpillars face constant danger in the wild, and their soft bodies make them easy targets for many animals. Birds are among their most common predators, combing branches and leaves in search of these nutrient-rich larvae. Wasps also prey on caterpillars. Some hunt them to feed their young, while others paralyze them and store them inside nests. Even small mammals, such as shrews and rodents, will eat caterpillars when the opportunity arises.

Caterpillar life cycle

The transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly is called metamorphosis, one of nature’s most extraordinary processes. Some caterpillars complete this change within weeks, while others may take years, depending on their species and climate. Across all butterflies, the life cycle follows four distinct stages: Egg → Caterpillar (larva) → Chrysalis (pupa) → Butterfly (adult).

Caterpillar to butterfly metamorphosis

Egg: An egg is the first stage of the life cycle, this stage is between 3 and 7 days, depending on the species of the butterfly. Generally, eggs are laid by female butterflies on leaves. They can be different in size, shape, and colour, but they are always small.

Larva: The larva is the next stage that lasts 2 or more weeks, depending on the species, available food, and other environmental conditions. In this stage, the tiny caterpillar hatches from the eggs and spends most of their time eating and growing. They shed their skin when they grow.

Pupa: The next stage is the pupa, also known as a chrysalis which lasts a week or two. Chrysalises are different for different species of butterflies. Many caterpillars hang upside down during this stage.

Adult: The last stage is the adult stage, turning into a butterfly. During this phase, butterflies emerge from their chrysalises with fully developed wings in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and vibrant colors. They are now able to fly, search for mates, the female lay eggs and the life cycle continues.

What is pupation? Why does a caterpillar turn into a pupa?

Pupation refers to the stage when a caterpillar stops growing and undergoes a rapid and remarkable physical transformation. During this phase, the caterpillar forms a protective casing either a chrysalis or a cocoon (depending on whether it’s a butterfly caterpillar or moth caterpillar) and begins reorganizing its entire body. Tissues break down, new structures develop, and the larva reshapes itself into a moth or butterfly.

A caterpillar becomes a pupa because this stage is essential for its metamorphosis. The larval body is designed for eating and growing, not for flight or reproduction. Inside the pupa, it rebuilds itself into an adult form capable of flying, finding mates, and continuing the species.

Conservation Status and Threats

Conservation status

Most caterpillar species are not assessed by IUCN Red List, however, when an adult species is rare or threatened, its caterpillar stage faces the same risks.

Species such as the striking Teinopalpus imperialis, was listed as Near threatened in the Red Data Book. As their habitats shrink and environmental pressures increase, the survival of their larvae is equally at risk.

Threats

Caterpillars face a wide range of threats and habitat loss remains one of the most significant pressures, as forests, grasslands, and plant-rich environments are cleared or fragmented. Without the specific host plants they rely on, many species struggle to complete their life cycles.

Pesticides and chemical pollution also pose serious dangers as these substances contaminate leaves, the caterpillars’ primary food source and can kill larvae outright or disrupt their development. Climate change adds another layer of stress, altering temperatures, rainfall patterns, and seasonal cues that caterpillars depend on for growth and metamorphosis.

In addition, invasive species and parasitoids threaten native caterpillar populations. Predatory insects and parasitic wasps can overwhelm local species, while introduced plants may replace the native vegetation caterpillars require. Together, these threats create a complex and growing challenge for caterpillars across the world.

Meeting Caterpillar

Caterpillars can be fascinating to watch, but some can deliver a painful sting. Whether you’re in your garden or walking a forest trail, you’ve likely seen one before but do you know the simple safety tips to follow when you do?

- Observe the caterpillar without touching it. Some species carry hairs or spines that can irritate or sting the skin.

- Never touch a caterpillar bare hands. If a caterpillar is in danger or happens to block a path, you can help by gently moving it with a leaf or a small stick, never with bare hands. This keeps both you and the caterpillar safe.

- If you’re stung by a caterpillar, use tape (or the adhesive part of a bandage) to remove hair or spines from the skin. In addition, use soap and warm water to wash the area thoroughly.

- Seek medical attention if swelling, intense pain, or allergic reactions appear. Respectful distance is always the safest way to appreciate these remarkable creatures.

What to know about Caterpillar rash?

A “caterpillar rash” refers to the skin reaction that occurs when a person comes into contact with certain species of butterfly or moth caterpillars. Most reactions are mild and fade on their own, but some can be more serious. The rash usually appears as redness, itching, or bumps on the skin. In a few cases, the reaction becomes systemic meaning it affects the body beyond the skin and may cause symptoms such as nausea or general discomfort.

Highly venomous puss caterpillar on a leaf

Out of nearly 165,000 caterpillar species worldwide, only about 150 are known to be harmful to humans, including around 50 species in the United States. Among them, the most dangerous is the asp caterpillar (Megalopyge opercularis), the larval form of the flannel moth. Often called the “puss caterpillar,” its soft, furry appearance hides venomous spines capable of causing intense pain and strong reactions. The pain from its sting was described to be more intense than that of a bee or jellyfish.

Interesting Facts about Caterpillar

- Butterfly caterpillars cannot sting, only some that turn into moth can

- Caterpillars are voracious eating machines

- A caterpillar’s first meal is its eggshell

- Some caterpillars can make funny clicking noises or spit out yucky liquid to scare birds and animals who want to eat them

- Caterpillars move in a wavelike motion. They do not walk using their thoracic legs or prolegs alone. Instead, they move forward by coordinating waves of body contractions that push them ahead.

- Not all caterpillar turn into butterflies

Reference

- Brackenbury, J. (1997). Caterpillar kinematics. Nature, 390(6659), 453–453.

- Coley, P. D., Bateman, M. L., & Kursar, T. A. (2006). The effects of plant quality on caterpillar growth and defense against natural enemies. Oikos, 115(2), 219–228.

- James, D. G. (Ed.). (2017). The book of caterpillars: A life-size guide to six hundred species from around the world. University of Chicago Press.

- Kitcher, P. (2008). Carnap and the caterpillar. Philosophical Topics, 36(1), 111–127.

- López-Pintado, O., García-Bañuelos, L., Dumas, M., & Weber, I. (2017). Caterpillar: A Blockchain-Based Business Process Management System. BPM (Demos), 172, 1–5.

- Snodgrass, R. E. (1961). The caterpillar and the butterfly.