Did you know one of the world’s most loyal birds is the hornbill? These striking birds belong to the family Bucerotidae and live in sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, the Philippines, and the Solomon Islands. Naturalists admire them for their impressive size, bold colors, and unusual heavy bill. Hornbills are also famous for their extraordinary breeding behavior: the female seals herself inside a tree cavity while the male feeds her for months. With their loud calls, dramatic casques, and essential role as seed dispersers, hornbills remain one of the most fascinating species in tropical forests.

| Common name | Hornbill |

|---|

| Scientific name | Family Bucerotidae |

|---|

| Taxonomy

|

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Bucerotiformes

Family: Bucerotidae

|

| Weight / Size | Small species: 30–32 cm, ~100 g. Large species: 90–100 cm; 3.7–6.3 kg; wingspan up to 180 cm. |

|---|

| Lifespan | Wild: 40 years. Captive: up to 60–90 years. |

|---|

| Population | Varies widely by species; many Asian species are declining. |

|---|

| Habitat | Tropical and subtropical forests, rainforests, woodland edges, savannas, and mature old-growth forests with large nesting trees. |

|---|

| Range | Sub-Saharan Africa; Indian subcontinent; Southeast Asia; Indonesia; Philippines; and the Solomon Islands. |

|---|

| Diet | Omnivorous — mainly fruits (especially figs), plus insects, small reptiles, small birds, and mammals. |

|---|

| Conservation status | Ranges from Least Concern to Critically Endangered, depending on species. |

|---|

Physical Characteristics of Hornbill

Hornbills show remarkable variation in size and color. They range from tiny, pigeon-sized species to large birds with wingspans reaching 6 feet (1.8 m). The smallest hornbill species are the Black Dwarf Hornbill (Tockus hartlaubi) and the Red-billed Dwarf Hornbill (Tockus camurus). They are only about 30–32 cm long and weigh under 100g.

The largest hornbill species is the Southern Ground Hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri). It stands 90–100 cm tall, weighs 3.7–6.3 kg, and has a wingspan of around 180 cm.

Hornbills have several unique anatomical traits. They are the only birds with the first two neck vertebrae fused, helping support their heavy, downward-curved bill. The bill is strong and multifunctional, used for feeding, nest building, fighting, and dispersing large seeds. In Great Hornbills, the bill and casque together can make up around 11% of the bird’s body weight.

Most species also have a casque, a helmet-like structure on the upper mandible. It strengthens the bill, amplifies calls, and plays a role in courtship displays. Eye and casque color can signal sex: male Great Hornbills have red eyes and a flat black-edged casque, while females have blue-white eyes and a smaller casque.

Hornbill plumage is typically black, grey, white, or brown, often contrasted by bright bill colors or bare facial skin. Some species even “paint” their bills with secretions from a tail gland, creating orange or red-yellow hues.

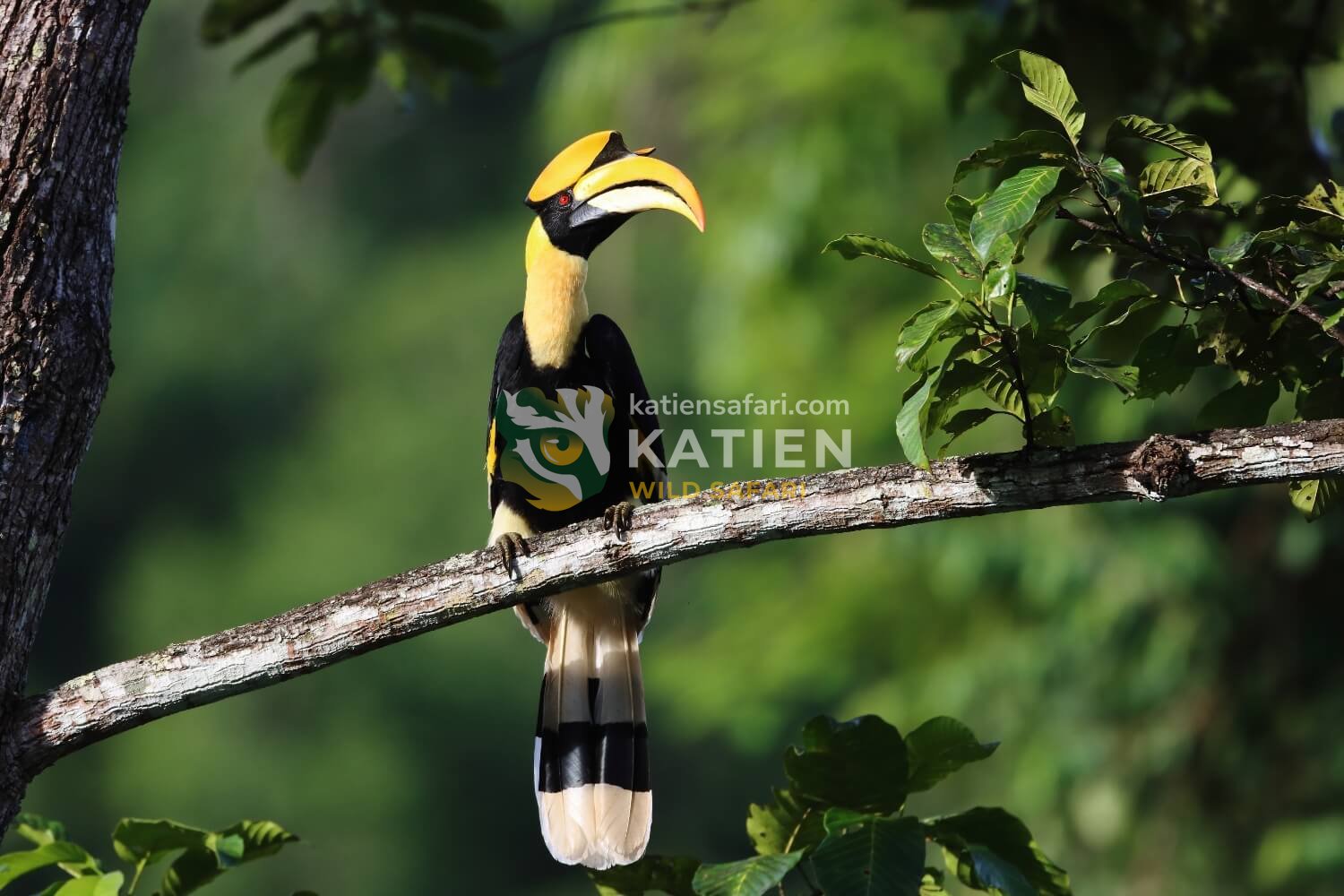

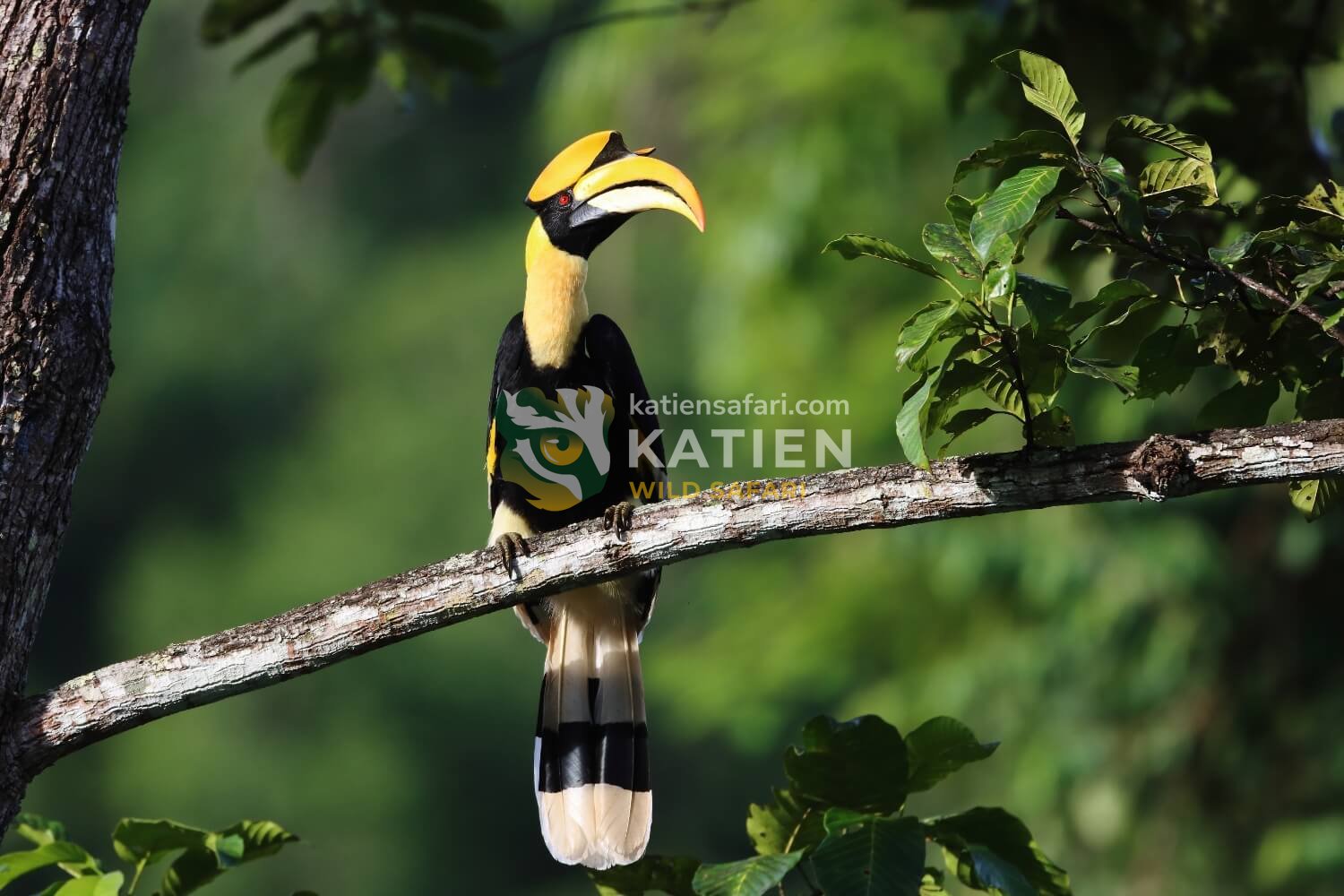

Hornbills show bold bills, strong plumage, and striking facial colors.

Subspecies of Hornbill

There are 62 hornbill species worldwide, 32 in Asia and 30 in Africa. Across these species, hundreds of subspecies exist, reflecting differences in geography, habitat, and isolated island populations.

Asian hornbills show the highest subspecies diversity. Many species have island-based subspecies, especially in Indonesia and the Philippines. The Philippines alone has 11 species, each divided into several subspecies restricted to single islands or island groups. These small, isolated populations are among the most threatened hornbill lineages.

The Helmeted Hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) has multiple subspecies distributed across Sumatra, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula. Although grouped under one species, regional populations show differences in casque shape and vocalizations.

The Great Hornbill (Buceros bicornis) also includes several subspecies across South and Southeast Asia, with slight variations in plumage shade, casque size, and soft-part coloration.

In contrast, African hornbills have fewer subspecies overall. Many species occur across large savanna belts with fewer geographic barriers, resulting in more uniform populations. However, some forest-dwelling African species—like the Black-and-white Casqued Hornbill—do contain distinct regional subspecies linked to Central and West African rainforest blocks.

Because many subspecies live in small, isolated habitats, 26 hornbill species (and many of their subspecies) are now globally threatened or near threatened. Island subspecies in the Philippines, including the Sulu Hornbill and Rufous-headed Hornbill, face the highest extinction risk, with some having fewer than 20 breeding pairs remaining.

The Great Hornbill displays a massive casque and vivid yellow-black wings.

Global Distribution and Habitat

Hornbills belong to the family Bucerotidae and are found across the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Melanesia. Although their range is wide, each region supports its own distinct group of species.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 24 species are recorded. Thirteen live in open woodlands and savannas, while the others prefer dense forest habitats. Across the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, hornbills are mostly forest birds, and only one species occurs in open savanna.

Further south, Indonesia hosts 13 species, including nine in Sumatra and others on Sumba, Sulawesi, Kalimantan, and Papua. The Philippines is another major hotspot, with 11 species—all of them island endemics. Because they live on small islands, many of these species are among the most threatened hornbills in the world.

One of the most widespread species is the Great Hornbill, which occurs from India through Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Peninsular Malaysia, all the way to Sumatra. Some hornbill species also reach the Philippines and the Solomon Islands.

A key point is that no hornbill genus is shared between Africa and Asia, showing how these lineages evolved separately.

African hornbills roam dry savannas and hunt insects from the ground.

Types of Hornbill Habitat

Hornbills live in many different environments, but most species depend on trees, especially large, old trees for nesting. In Asia, hornbills are mainly forest specialists. They spend most of their time in the canopy and rely on mature, moist forests with tall trees for nesting. Without these forests, many species would be unable to survive.

Other hornbills prefer open woodlands or savannas. Ground hornbills, such as Bucorvus, are mostly terrestrial and walk widely across open grasslands. Some adaptable species also use farmlands, plantations, parks, and other modified landscapes, as long as suitable trees remain.

A few African dwarf hornbills can even survive in very dry, arid environments, showing how diverse this family can be. The Oriental Pied Hornbill is one of the most flexible species. It lives along forest edges from coastal lowlands up to 700 m, and it can also appear in mangroves, plantations, and urban green areas.

Hornbill in Vietnam

Vietnam is home to five hornbill species:

- Great Hornbill (Buceros bicornis)

- Wreathed Hornbill (Rhyticeros undulatus)

- Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris)

- Brown Hornbill (Anorrhinus austeni)

- Rufous-necked Hornbill (Aceros nipalensis) – extremely rare

These species occur mainly in large primary forests, including Cat Tien, Yok Don, Kon Ka Kinh – Kon Chu Rang, Pu Mat, Cuc Phuong, Bach Ma, and Phong Dien. Older records also show past sightings in Hoang Lien Son and Cat Ba.

The Oriental Pied Hornbill is the easiest to see in Vietnam because it adapts well to different habitats. The Great Hornbill and Wreathed Hornbill are much rarer, and the Rufous-necked Hornbill has nearly disappeared, likely becoming locally extinct in several areas.

The Oriental Pied Hornbill often thrives near forest edges.

Hornbill in Cat Tien National Park

Cat Tien National Park is one of Vietnam’s key hornbill habitats, with large tracts of old-growth forest that provide the tall nesting trees hornbills depend on. The Great Hornbill is the most iconic species here, easily recognized by its huge yellow bill and casque. Although exact numbers are unknown, Cat Tien remains a stronghold for this bird.

During the breeding season, Great Hornbills often nest in spung trees, whose tall trunks and large natural cavities match the hornbill’s large size and preference for high roosting spots. Because of this dependence on mature hardwoods, the species is considered an indicator of healthy, old-growth forest.

Cat Tien’s hornbills glide over tall canopies at dawn and dusk.

Diet and Predators

Diet

Hornbills are omnivores, but fruit is their main food source. They rely heavily on figs, which are considered the “supermarket trees” of the rainforest. Species like the Great Hornbill and the Indian Grey Hornbill feed almost entirely on figs during the breeding season. They also eat wild nutmeg and many high-lipid forest fruits, which give them the energy needed for long flights and raising chicks.

Their diet covers a wide range of tropical fruits, including those from native families such as the custard apple family, the laurel family, and many types of forest berries and wild drupes. Some species can even eat strychnine fruit, which is poisonous to many other animals.

Animal prey provides extra protein and minerals. Hornbills catch large insects such as grasshoppers, crickets, spiders, and scorpions, as well as frogs, lizards, small birds, and sometimes small mammals. Ground hornbills are powerful hunters and can even take venomous snakes.

Foraging Behavior

Hornbills forage during the day and usually travel as pairs or in small family groups. They move from tree to tree following seasonal fruiting, and their excellent memory helps them return to the same fruiting trees every year. This behavior allows them to save energy in dense forests where food can be scattered.

Their unique bill shape controls how they handle food. They pick fruits and prey using the tip of the bill like a “finger,” then toss the food into the air to swallow it because their tongue is very short. The edges of the bill have small serrations that help grip and cut slippery fruits. Some species also have a throat pouch that lets them store fruit temporarily while flying.

Predators & Defense

Large hornbills rarely face danger, but smaller species and chicks are often targeted by eagles, large owls, and tree-climbing predators. To stay safe, hornbills usually roost on thin branches at the edges of the canopy, where predators find it harder to reach them.

Hornbills form many interesting ecological interactions while feeding. Some species cooperate with dwarf mongooses by sharing warning signals about predators. Smaller hornbills may follow army ants or squirrels to catch insects that are flushed out. In Asia and Africa, elephants and bears also help indirectly by breaking branches and opening tree cavities, creating ideal spots for feeding or nesting.

Ecological Role

Hornbills play a vital role in keeping tropical forests alive. Their most important function is seed dispersal. As large fruit-eaters, they swallow whole fruits, carry them far from the parent tree, and later release the seeds intact, often with a natural “fertilizer boost.” Species like the Great Hornbill, Wreathed Hornbill, and Oriental Pied Hornbill are key dispersers of wild nutmeg and many rainforest trees.

Hornbills also help control pests. They eat insects, small reptiles, amphibians, and even small mammals. Ground hornbills are true carnivores, while species like the Malabar Grey Hornbill are valued by farmers for reducing crop pests.

Behavior and Social Structure

Hornbills are diurnal birds, and they have a strong social structure. They usually live as monogamous pairs or in small family groups. Outside the breeding season, however, they may gather in large communal roosts, with some sites recording more than 2,000 individuals resting together.

Most hornbills are arboreal and spend much of their time in the canopy. They sunbathe, preen, and communicate through a variety of calls. A few exceptions exist — ground hornbills live mainly on the savannas and spend most of their day walking on the ground.

During roosting, hornbills choose thin branches at the edges of the canopy. These spots make it harder for climbing predators to reach them, while still providing cover from aerial attacks thanks to the surrounding foliage.

Hornbills use many forms of communication, including both vocal and visual signals. They also produce mechanical communication: the loud, rushing wing sounds heard during flight. This noise acts as an identification signal and helps members of the group recognize each other.

A male Great Hornbill offers fruit to court the perched female.

Breeding and Reproduction

Hornbills have one of the most remarkable breeding strategies in the bird world. They nest in natural tree cavities and form long-lasting monogamous pairs. Many species show strong nest-site fidelity and may return to the same cavity for decades.

The breeding season usually occurs from January to August, depending on the region and species. When the female enters the nest cavity, she seals herself inside using mud, fruit pulp, and droppings, leaving only a narrow slit. This unique defensive strategy, characteristic of the subfamily Bucerotinae, protects the female and her developing chicks from predators and rival hornbills.

Once sealed inside, the female lays 1–6 eggs, depending on the species; larger hornbills typically lay only one or two. The eggs are incubated by the female for 38–40 days. Because the eggs are laid several days apart, the chicks hatch asynchronously. The older chick often has a survival advantage, and brood reduction may occur.

Hornbills have a long, energy-intensive breeding cycle that can last about 4 months. During this entire period, the female and chicks depend completely on the male for food. This reliance makes hornbills a powerful symbol of loyalty and devotion. If the male fails to return, due to predation or danger, the female and the chicks may starve.

After hatching, chicks grow slowly. They make their first flights at around two months old but continue following their parents to learn essential foraging and survival skills. The age at which they reach maturity varies among species.

The male Great Hornbill brings fruit to feed the nesting female.

Threat and Conservation

Threat

Habitat loss and forest fragmentation are the most serious and long-term threats to hornbills. This is especially true in the lowland forests of Southeast Asia, where logging, agricultural expansion, and urban development have rapidly erased large, continuous forest blocks.

Illegal hunting and wildlife trade also place heavy pressure on many species. The Great Hornbill is hunted for meat, fat, tail feathers, and its casque, which is used for ornaments. The Helmeted Hornbill faces an even more severe crisis because its solid casque, often called “hornbill ivory,” is highly valued for carving and sold at high prices in China and Japan.

The loss of nesting trees further increases extinction risk. In many logged forests, almost all old trees are removed, leaving only small, unsafe cavities that cannot support successful breeding. As suitable nest sites shrink, competition between individuals and species becomes intense.

Several Asian endemics are now on the brink of extinction. The Sulu Hornbill has fewer than 20 breeding pairs left. Other species, such as the Rufous-headed Hornbill and the Visayan Hornbill, are also rapidly declining due to a combination of deforestation, traditional hunting, and illegal logging. In contrast, most African hornbill species remain less threatened because savanna habitats are more extensive and hunting pressure is generally lower.

Conservation

Legal protection and long-term research programs play an essential role in safeguarding hornbill populations. The Great Hornbill is listed in CITES Appendix I, which restricts international trade, while the Helmeted Hornbill is classified as Critically Endangered to strengthen global protection.

Community-based conservation has shown strong results. In Thailand and India, the “hornbill nest adoption” model allows local communities to protect individual nest trees, monitor breeding pairs, and receive support or income in return.

Habitat management and nest restoration efforts are also helping struggling populations. Artificial nest boxes have been installed in several regions of Thailand and southern India, providing safe nesting sites where old trees have disappeared.

Anti-poaching and anti-trafficking campaigns in key hotspots like Kerinci Seblat (Sumatra) are working to disrupt the supply chain for hornbill ivory, reducing pressure on the Helmeted Hornbill and helping stabilize the remaining wild populations.

Responsible Hornbill Encounters with Katien Safari

Joining a Katien Safari tour in Cat Tien National Park offers a respectful way to see hornbills in the wild. The company partners with park rangers to lead small groups into key forest areas while ensuring the birds’ natural behavior is never disturbed. Visitors may spot species such as the Great Hornbill or Oriental Pied Hornbill as they glide through the canopy.

Field-tested tips for better hornbill watching:

- Arrive before sunrise when hornbills are most active.

- Keep a minimum distance of 50–70 m from nest trees.

- Avoid strong colors; wear green, brown, or earth tones.

- Turn off the camera flash and use silent-shutter mode.

- Stay on the trail and avoid standing directly under fruiting trees.

- Move slowly, pause often, and let the birds come into view naturally.

5 Interesting Facts about Hornbill

- Hornbill ivory is extremely valuable. The solid casque of the Helmeted Hornbill can sell for about USD 6,150 per kilogram, making it roughly 3 times more expensive than elephant ivory.

- Hornbills have very short tongues, so they can’t swallow food from the bill tip. They flick their heads to toss it straight into their throat.

- Their wings create a powerful sound. The Great Hornbill’s wings produce a loud whooshing noise in flight, often compared to the sound of a steam train rushing through the forest.

- Thailand honors its loyalty. Since 1997, February 13 has been celebrated as Hornbill Day in Thailand, symbolizing love and lifelong partnership, just one day before Valentine’s Day.

- The Great Hornbill is the official state bird of Kerala, India, symbolizing strength, longevity, and the beauty of the region’s tropical forests.

Reference

- BirdLife International. (2020). Buceros bicornis (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22682453A184603863). IUCN. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22682453A184603863.en

- Fauna & Flora. (n.d.). Hornbills: Exotic and critically endangered. Unpublished web article.

- Hornbill Specialist Group. (2022). Hornbill natural history and conservation (Vol. 3). IUCN SSC. https://iucnhornbills.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/HNHC_Volume-3.pdf

- Raman, T. R. S., & Mudappa, D. (1998). Hornbills: Giants among the forest birds. Resonance, 3(8), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02837346

- San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. (2025). Hornbill. San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants.

- WWF. (2024). Amazing animals: Hornbills. In H. L. Timmins, S. Stolton, N. Dudley, M. Kinnaird, W. Elliott, M. Momanyi, & B. Chaplin-Kramer (Authors), Nature’s technicians: The amazing ways in which animals maintain our world (pp. xx–xx). WWF.